This post concludes my series on Belle Northrup’s article. The other two posts can be found here. One thing I would like to mention is that I have included all of the information and examples in Northrup’s article in these posts. There are no examples left out.

This post will deal with what is probably most interesting to all of you: yin and yang in women. Before we begin, however, I need to make an important point. For some reason, there is the misconception in the color and style community that Belle Northrup created the types that we are familiar with (Classic, Natural, Gamine, etc.) and McJimsey simply wrote them down. The only reference I have found for Northrup and something vaguely resembling these types is found here–see “Athletic Girl in Subdued Colors.”

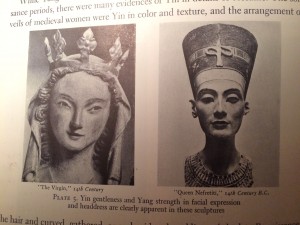

With that out of the way, let’s move on to what Northrup did talk about. Northrup’s reason for talking about yin and yang in nature, architecture, art, and music is “to set up a clear and meaningful personality scale so that we may learn more easily to appraise ourselves and others.” We are to set up a personality scale with yin gentleness at one end, and yang strength on the other.

The women she uses for her examples of yin are Janet Gaynor, Joan Bennett, Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, Helen Chandler, and Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

(Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

The women she uses for her examples of yang are Greta Garbo, Alla Nazimova, Katharine Cornell, Helen Wills Moody, Kay Francis, and Jane Addams.

(Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

From the theater, we have the characters of Electra, Cleopatra, and Lady Macbeth (no mention of whether they are yin or yang; I am going to guess that Electra is yin and Cleopatra and Lady Macbeth are yang, but I welcome other ideas in the comments); yin Mignon and Mimi; and Yang Aida and Brunhilde.

Northrup says we can also associate yin and yang women with flowers, trees, or buildings. Some yin women are birch trees, trim and delicate. Some yin children are gentle and flowerlike, and thus reminiscent of sweet peas or Queen Anne’s lace. In contrast, there are yang girls and women who remind us of the pine and the oak, and calla lilies rather than lily of the valley. They are the march and not the minuet; they are the cathedral and not the cottage.

Janet Gaynor and Greta Garbo are the two Northrup uses to epitomize the opposition of extreme yin and extreme yang. Some individuals on the list earlier may be less yin or yang, but extremes nonetheless. She says that this suggests that we can use this scale as a gauge, from Gaynor to Garbo.

Yin qualities are gentleness, delicacy, demureness, lightness, grace, piquancy, naiveté, and youth. Yang qualities are strength, force, dignity, power, serenity, vigor, sophistication, and maturity.

YIN

Physique: short, slight, graceful

Coloring: fair, light hair

Head: delicately poised

Features: small, rounded

Facial Expression: gentle, winsome

Voice: soft, light, mild

Walk: tripping, easy

YANG

Physique: tall, strong, erect

Coloring: dark hair, eyes

Head: well set on steady shoulders

Facial Expression: direct, forceful

Voice: deep, clear

Walk: strong, firm

Northrup adds that both yin and yang traits will always be seen as positives for these purposes. Yin is not weakness, frailty, and subjection, but instead gentleness, mildness, and delicacy. Yang is not aggressiveness, crudeness, or overbearing mannishness, but instead strength, poise, and dignity.

Extremely yang people are tall, dark, and strongly built. Their voices are deep, their features are forceful and well molded but not small, and their eyes are direct. Extremely yin people are short, light, and fair, with small features and soft voices. There is an ease and a lightness in their body movements.

(Source)

By establishing these opposites of what Northrup calls “personality-expression,” we can set up a scale to be used to interpret and understand not only extremes like Garbo and Gaynor, but the larger majority of people who fall somewhere along this scale.

Like in art and music, each woman has an intermingling of yin and yang. The subtlety of this intermingling makes each woman a “fascinating, individual study.” Northrup does not want to make women into yin/yang “types,” but “to see clearly their possibilities and limitations of personality-appearance with a view to dressing them accordingly.”

To understand the yin/yang balance of an individual, we should observe the person as a whole. We learn that ”

…each of her individual traits depends upon the others and forms the sum total of her personality. We will not then rate this person as a “type” because she has blonde hair or is tall and willowy–partial and inadequate judgements–but we will form a picture of her in her completeness. No one part will be overemphasized, and a fairer, broader basis for dress selection will be established.

Northrup says that during this process, you will often find hidden, attractive qualities in both personality and appearance in a person that you will want to emphasize. Using yin and yang, we can get an insight into someone’s “essential and interesting” personality. Once we have learned to appraise and “see” an individual or ourselves, the answers to problems of dress become clear.

Once you know what you are aiming for, what you want to express in a person’s appearance, selecting or designing clothes becomes even more interesting and significant.

That is how she ends the paper, and unfortunately, it seems to be where our access to her theory and methods ends as well. This paper was supposed to be a chapter of a longer book, which I assume would have gone into depth about both how to evaluate a person’s personality-appearance, and how to design for it. From what I can find, this book never materialized. This article has Northrup telling us what 1939 fashions would be suitable for yin and yang types.

I hope that you have found these interesting and helpful. If you have any information or sources that I haven’t covered here, please let me know.